Introduction

The U.S. Department of Education (Department) is committed to supporting the use of

technology to improve teaching and learning and to support innovation throughout educational

systems. This report addresses the clear need for sharing knowledge and developing policies for

“Artificial Intelligence,” a rapidly advancing class of foundational capabilities which are

increasingly embedded in all types of educational technology systems and are also available to

the public.

We will consider “educational technology” (edtech) to include both (a) technologies

specifically designed for educational use, as well as (b) general technologies that are widely used

in educational settings. Recommendations in this report seek to engage teachers, educational

leaders, policy makers, researchers, and educational technology innovators and providers as they

work together on pressing policy issues that arise as Artificial Intelligence (AI) is used in

education.

AI can be defined as “automation based on associations.” When computers automate reasoning

based on associations in data (or associations deduced from expert knowledge), two shifts

fundamental to AI occur and shift computing beyond conventional edtech:

(1) from capturing data to detecting patterns in data and

(2) from providing access to instructional resources to automating decisions about instruction and other educational processes. Detecting patterns and automating decisions are leaps in the level of responsibilities that can be delegated to a computer system.

The process of developing an AI system may lead to bias in how patterns are detected

and unfairness in how decisions are automated. Thus, educational systems must govern their use

of AI systems. This report describes opportunities for using AI to improve education, recognizes

challenges that will arise, and develops recommendations to guide further policy development.

Rising Interest in AI in Education

Today, many priorities for improvements to teaching and learning are unmet. Educators seek

technology-enhanced approaches addressing these priorities that would be safe, effective, and

scalable. Naturally, educators wonder if the rapid advances in technology in everyday lives could

help. Like all of us, educators use AI-powered services in their everyday lives, such as voice

assistants in their homes; tools that can correct grammar, complete sentences, and write essays;

and automated trip planning on their phones. Many educators are actively exploring AI tools as

they are newly released to the public1.

Educators see opportunities to use AI-powered capabilities

like speech recognition to increase the support available to students with disabilities, multilingual

learners, and others who could benefit from greater adaptivity and personalization in digital

tools for learning. They are exploring how AI can enable writing or improving lessons, as well as

their process for finding, choosing, and adapting material for use in their lessons.

Educators are also aware of new risks. Useful, powerful functionality can also be accompanied

with new data privacy and security risks. Educators recognize that AI can automatically produce

output that is inappropriate or wrong. They are wary that the associations or automations

created by AI may amplify unwanted biases. They have noted new ways in which students may

1 Walton Family Foundation (March 1, 2023). Teachers and students embrace ChatGPT for education.

https://www.waltonfamilyfoundation.org/learning/teachers-and-students-embrace-chatgpt-for-education2

represent others’ work as their own. They are well-aware of “teachable moments” and pedagogical strategies that a human teacher can address but are undetected or misunderstood by AI models. They worry whether recommendations suggested by an algorithm would be fair.

Educators’ concerns are manifold. Everyone in education has a responsibility to harness the good to serve educational priorities while also protecting against the dangers that may arise as a result of AI being integrated in edtech.

To develop guidance for edtech, the Department works closely with educational constituents.

These constituents include educational leaders—teachers, faculty, support staff, and other educators—researchers; policymakers; advocates and funders; technology developers;community members and organizations; and, above all, learners and their families/caregivers.

Recently, through its activities with constituents, the Department noticed a sharp rise in interest

and concern about AI.

For example, a 2021 field scan found that developers of all kinds of technology systems—for student information, classroom instruction, school logistics, parentteacher communication, and more—expect to add AI capabilities to their systems. Through a series of four listening sessions conducted in June and August 2022 and attended by more than 700 attendees, it became clear that constituents believe that action is required now in order to get ahead of the expected increase of AI in education technology—and they want to roll up their sleeves and start working together. In late 2022 and early 2023, the public became aware of new generative AI chatbots and began to explore how AI could be used to write essays, create lesson plans, produce images, create personalized assignments for students, and more.

From public expression in social media, at conferences, and in news media, the Department learned more about risks and benefits of AI-enabled chatbots. And yet this report will not focus on a specific AI

tool, service, or announcement, because AI-enabled systems evolve rapidly.

Finally, the Department engaged the educational policy expertise available internally and in its relationships with AI policy experts to shape the findings and recommendations in this report.

Three Reasons to Address AI in Education Now

“I strongly believe in the need for stakeholders to understand the cyclical effects of AI and education. By understanding how different activities

accrue, we have the ability to support virtuous cycles. Otherwise, we will

likely allow vicious cycles to perpetuate.”

—Lydia Liu

During the listening sessions, constituents articulated three reasons to address AI now:

First, AI may enable achieving educational priorities in better ways, at scale, and with lower costs. Addressing varied unfinished learning of students due to the pandemic is a policy priority, and AI may improve the adaptivity of learning resources to students’ strengths and needs. Improving teaching jobs is a priority, and via automated assistants or other tools, AI may provide teachers greater support. AI may also enable teachers to extend the support they offer to individual students when they run out of time. Developing resources that are responsive to the knowledge and experiences students bring to their learning—their community and cultural assets—is a priority, and AI may enable greater customizability of curricular resources to meet local needs.3

As seen in voice assistants, mapping tools, shopping recommendations, essay-writing capabilities,

and other familiar applications, AI may enhance educational services.

Second, urgency and importance arise through awareness of system-level risks and anxiety about

potential future risks. For example, students may become subject to greater surveillance. Some

teachers worry that they may be replaced—to the contrary, the Department firmly rejects the

idea that AI could replace teachers.

Examples of discrimination from algorithmic bias are on the public’s mind, such as a voice recognition system that doesn’t work as well with regional dialects,or an exam monitoring system that may unfairly identify some groups of students for disciplinary action. Some uses of AI may be infrastructural and invisible, which creates concerns about transparency and trust. AI often arrives in new applications with the aura of magic, but educators and procurement policies require that edtech show efficacy. AI may provide information that appears authentic, but actually is inaccurate or lacking a basis in reality.

Of the highest importance, AI brings new risks in addition to the well-known data privacy and data security risks, such as the risk of scaling pattern detectors and automations that result in “algorithmic discrimination” (e.g., systematic unfairness in the learning opportunities or

resources recommended to some populations of students).

Third, urgency arises because of the scale of possible unintended or unexpected consequences.

When AI enables instructional decisions to be automated at scale, educators may discover

unwanted consequences. In a simple example, if AI adapts by speeding curricular pace for some

students and by slowing the pace for other students (based on incomplete data, poor theories, or

biased assumptions about learning), achievement gaps could widen. In some cases, the quality of

available data may produce unexpected results.

For example, an AI-enabled teacher hiring system might be assumed to be more objective than human-based résumé scoring. Yet, if the AI system relies on poor quality historical data, it might de-prioritize candidates who could bring both diversity and talent to a school’s teaching workforce.

In summary, it is imperative to address AI in education now to realize key opportunities, prevent

and mitigate emergent risks, and tackle unintended consequences.

Toward Policies for AI in Education

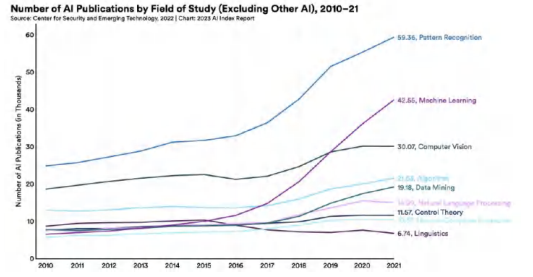

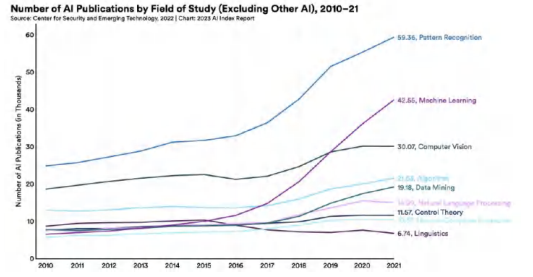

The 2023 AI Index Report from the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI has documented

notable acceleration of investment in AI as well as an increase of research on ethics, including

issues of fairness and transparency.2

Of course, research on topics like ethics is increasing because problems are observed. Ethical problems will occur in education, too.3

The report found a striking interest in 25 countries in the number of legislative proposals that specifically include AI. In the United States, multiple executive orders are focused on ensuring AI is trustworthy and

equitable, and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy has introduced a

2 Maslej, N., Fattorini, L., Brynjolfsson E., Etchemendy, J., Ligett, K., Lyons, T., Manyika, J., Ngo, H., Niebles, J.C., Parli, V.,Shoham, Y., Wald, R., Clark, J. and Perrault, R., (2023). The AI index 2023 annual report. Stanford University: AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI.

3 Holmes, W. & Porayska-Pomsta, K. (Eds.) (2022). The ethics of artificial intelligence in education. Routledge. ISBN 978-03673497214

Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights (Blueprint)4 that provides principles and practices that help

achieve this goal. These initiatives, along with other AI-related policy activities occurring in both

the executive and legislative branches, will guide the use of AI throughout all sectors of society.

In Europe, the European Commission recently released Ethical guidelines on the use of artificial

intelligence (AI) and data in teaching and learning for educators.5

AI is moving fast and heralding societal changes that require a national policy response. In addition to broad policies for all sectors of society, education-specific policies are needed to address new opportunities and challenges within existing frameworks that take into consideration federal student privacy laws (such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA), as well as similar state related laws.

AI also makes recommendations and takes actions automatically in support of student learning, and thus educators will need to consider how such recommendations and actions can comply with laws such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). We discuss specific policies in the concluding section.

Figure 1: Research about AI is growing rapidly. Other indicators, such as dollars invested and

number of people employed, show similar trends.

AI is advancing exponentially (see Figure 1), with powerful new AI features for generating images

and text becoming available to the public, and leading to changes in how people create text and

4 White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (October 2022), Blueprint for an AI bill of rights: Making automated systems work for the American people. The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/ai-bill-of-rights/

5 European Commission, Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. (2022). Ethical guidelines on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and data in teaching and learning for educators, Publications Office of the European

Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/1537565

The advances in AI are not only happening in research labs but also are making news in mainstream media and in educational-specific publications.

Researchers have articulated a range of concepts and frameworks for ethical AI7, as well as for related concepts such as equitable, responsible, and human-centered AI. Listening session

participants called for building on these concepts and frameworks but also recognized the need

to do more; participants noted a pressing need for guardrails and guidelines that make educational use of AI advances safe, especially given this accelerating pace of incorporation of AI into mainstream technologies. As policy development takes time, policy makers and educational constituents together need to start now to specify the requirements, disclosures, regulations, and

other structures that can shape a positive and safe future for all constituents—especially students

and teachers.

Policies are urgently needed to implement the following:

- leverage automation to advance learning outcomes while protecting human decision

making and judgment; - interrogate the underlying data quality in AI models to ensure fair and unbiased pattern

recognition and decision making in educational applications, based on accurate

information appropriate to the pedagogical situation; - enable examination of how particular AI technologies, as part of larger edtech or

educational systems, may increase or undermine equity for students; and - take steps to safeguard and advance equity, including providing for human checks and

balances and limiting any AI systems and tools that undermine equity

Need more information ? Please contact us.